Introduction

Plantar fasciitis involves the irritation of the plantar fascia, thick bands of tissue connecting the toes to the medial calcaneal tuberosity. The condition typically develops from excessive loading or overuse. It often presents with a sharp pain along the proximal plantar fascia and around its attachment in the calcaneal tuberosity that usually worsens with prolonged standing or physical activity, as well as upon standing after a long rest period.

According to the RACP, around 4-7% of Australians develop plantar fasciitis at some point in their lives. While ~10% of these cases may require more invasive therapies, the other 90% will improve in 3-6 months with the right conservative approach.

The biomechanics of plantar fasciitis

Understanding the biomechanics of the foot and plantar fasciitis is essential to prescribing the right orthosis and treatment plan. The plantar fascia is made up of type 1 collagen, which has a triple-helix structure and long, longitudinally facing fibrocytes that run parallel to each other. As a result of this structure, the fascia has excellent tensile strength and flexibility. Fascia fibres are also highly effective at transmitting and redistributing longitudinal force (i.e., forces that run parallel to the direction of the fascia).

In the ideal foot, the plantar fascia supports the arch and regulates pronation and supination during the gait cycle. When the metatarsals bend, the fascia acts as a cord during propulsion and as a truss when the foot absorbs impact from ground strike.

However, excess forces from pronation, supination, and compression can begin degrading these fibres. Contributing factors include:

- Long periods of standing provide a constant compressive force to the foot.

- Long periods of running or walking increase the strain on the plantar fascia. Sustained periods of running, such as during a marathon, can lead to overuse and microtrauma in the tissues, even with a perfect gait cycle and supportive shoes.

- Weakness in the tibialis posterior increases tensile forces in the fascia. This muscle plays a crucial role in arch support and inversion, so its insufficiency places more stress on the fascia.

- A tight Achilles tendon reduces the foot’s dorsiflexion range, which causes excess pronation as other structures in the foot try to compensate.

-

High arches can’t as effectively redistribute shock from ground strike.

Due to the damage to the collagen matrix associated with the condition, the fascia grows thicker (>0.3 mm in symptomatic heels vs 0.2mm in asymptomatic) and loses some of its elasticity. As a result, patients often feel a sharp pain at the insertion point in the calcaneus that’s at its worst upon waking and taking the first few steps. The pain improves and worsens again when the plantar fascia is subjected to similar supination, pronation, and compression forces that initially caused the damage.

Orthotics for Plantar Fasciitis

A systematic review found that mechanical treatments, such as night splints, insoles, heel pads, and shoe modifications (e.g., rocker soles), were effective in relieving plantar fasciitis pain and improving foot function.

Insoles

Research shows insoles can effectively improve pain and function and reduce plantar pressure. They can provide medial arch support and greater midfoot contact for proper weight redistribution, reducing pressure on the plantar fascia.

However, not all insoles are created equal. While many studies found no notable difference between a prefabricated and a custom insole in terms of pain relief and functional improvement, there is a notable difference based on how they are made.

One study into three insoles found that our ErgoPad Redux Heel performed best, with less pain experienced from the outset of the study and significantly reduced pain at the 3-week mark compared to the two other insoles.

The ErgoPad achieves this through a thin, self-supporting plastic core with a central plantar heel recess and a fan-shaped extension to reduce pressure on the fascia at the calcaneus attachment point. A soft foam layer lining the core provides cushioning for further relief and patient comfort.

To ensure compliance, the insoles are available in various lengths and widths and can securely fit almost any shoe.

Heel pads

Heel pads can also be effective in relieving plantar fasciitis. In fact, one study found that combining night splints with viscoelastic heel pads and stretching was ~89% effective in treating the condition.

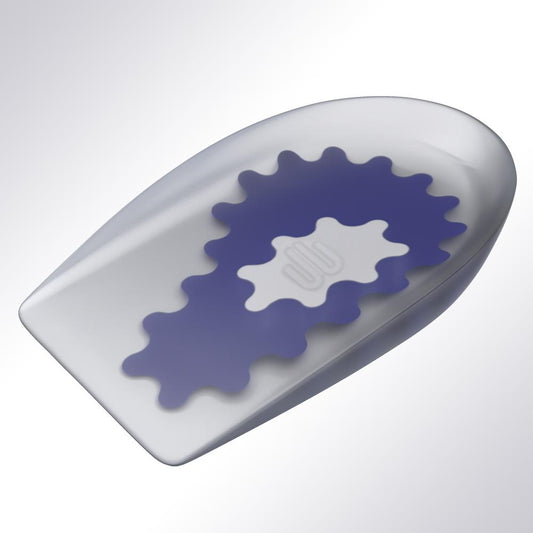

Our ViscoSpot Heel Cushion achieves this by combining three specialised zones:

- A soft, inner white layer to provide targeted cushioning

- A firmer middle blue to relieve pain and strain on the foot tendons and the plantar fascia

- And a firm, outer grey layer to guide the roll of the foot, reducing undue stress on affected structures

Additionally, the stress placed on the plantar fascia during walking is proportional to the Achilles tendon force, which, in turn, is proportional to the magnitude of heel rise. As the insert slightly elevates the heel, it reduces heel rise during gait, further reducing fascia strain.

Plantar fasciitis night splint

Plantar fasciitis pain is at its worst when taking the first few steps out of bed, as the fascia contracts while we sleep. Wearing a night splint designed for the condition will keep the ankle dorsiflexed, and the fascia lengthened, reducing the tension and pain and promoting healing.

Some studies report that participants saw improvement in 12 weeks of use, while others saw it in as little as 4 weeks.

The ideal brace will have a cushioned interior for better compliance. It should also have the structure to lock the ankle and foot in a dorsiflexed position, including straps and a 90-degree, anatomically shaped splint.

The b:joynz night splint also features an adjustable wedge so the patient can adjust the level of dorsiflexion.

Other conservative methods and the importance of a holistic approach for plantar pain relief

As previously mentioned, conservative therapies for plantar fasciitis generally work best together rather than alone. Studies show that combining various orthotics (rocker shoes with insoles or a night splint) and treatment methods (orthotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, gastrocnemius and soleus stretching) yielded better results. Additionally, some methods, like shockwave therapy, may work for certain patients but not for others, so it’s essential to work with them and find the best combination.

Medicated pain relief

NSAIDS were brought into question as plantar fasciitis is a degenerative process, not an inflammatory one. Some studies indicate they had no beneficial effects, while others recommend using them in conjunction with other treatment modalities for higher effectiveness and relief. It is best to discuss analgesic options and dosages with the patient and work with them to determine if such medications will benefit their treatment plan.

In more severe plantar fascia pain cases, cortisone shots may be prescribed. However, it is best to exercise caution as some studies indicate they may result in fat pad atrophy (which can worsen the condition) or plantar fascia rupture (as the patient will find it harder to determine which movements agitate the fibres).

Physical therapy

A systematic review found that stretching the plantar fascia and triceps surae effectively relieved fasciitis symptoms. This is based on biomechanical principles: tight calves and Achilles tendons result in altered gait mechanics, placing greater stress on the plantar fascia.

Studies generally recommend three stretching sessions per day consisting of:

- A plantar fascia stretch involves using one hand to slowly bend back the toes. The patient may then use the other hand to palpate the arch and see if the plantar fascia is taut, indicating the right stretch amount.

- A wall calf stretch, where the patient places the affected foot behind them with its heel firmly on the floor and leans forward.

Patients may also benefit from some strengthening exercises, particularly calf raises with a rubber ball placed between the ankles. Unlike regular calf raises, this variant targets the tibialis posterior.

Physiotherapy

Myofascial release can help break down scar tissue that could be contributing to the tightness. Physiotherapists, osteopaths, and other clinicians are also key to guiding the patient through a tailored stretching and strengthening program and recommend other conservative or surgical treatment methods should the need arise.

Focal extracorporeal shockwave therapy

Electrotherapy has been shown to improve pain levels and function in certain patients. Ultrasound energy creates microtrauma in the plantar fascia, prompting a healing response. It can increase cell permeability, prompt the formation of new blood vessels, stimulate nerve endings, and break down calcifications. In the short term, it is a highly effective treatment for 40-80% of patients. However, long-term results are currently limited.

Certain studies in the systematic review also indicated that combining shock wave therapy with physical therapy yielded better results than either method alone.

Activity adjustment

Patients should also be advised to adjust or avoid certain aggravating activities, such as running. They may instead engage in low-weight-bearing sports, such as cycling and swimming.

Conclusion

Plantar fasciitis is a painful, self-limiting condition. It stems from external stressors or biomechanical issues in the ankle or foot. Fortunately, the condition responds well to conservative therapies involving pain relief and functional improvement. Current research shows that combining different modalities like night splinting, day insoles, stretching, and shockwave therapies yields the best results.